- Home

- Jason Porter

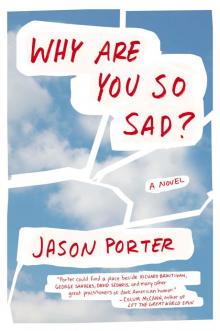

Why Are You So Sad? Page 2

Why Are You So Sad? Read online

Page 2

As a defense against the miserable fabric that covered the walls of my cubicle, I had posted as many photographs as I could find. Anything that might protect me from the obscene company pink. An amateur football player with turf caked on his helmet was crying in defeat. A bull with blood gushing out of its side was chasing after a matador. A frozen beach was littered with plastic bottles and dead seagulls. Some were photos I had taken. Others were cut out from magazines or the newspaper. One of my favorites, of a child soldier, stared down from above my monitor. He was pointing an automatic weapon at me. According to the magazine article about him, he was hardened by cheap drugs forced on him by his captors and from an adolescence that consisted of firing on villagers from the back of a pickup.

I wondered how he would answer my survey.

—I am single.

—I am too young to have an affair.

—What does “future self” mean?

—I believe in death after death after death.

—I like sports. We play soccer, but then somebody shoots at the ball with a gun because they lost, and I want to cry but am afraid that if they see me cry I will get shot or left behind.

—I am sad because my father has been replaced by a teenager in sunglasses. And this same teenager raped my mother before killing her, and now my choice is to be his friend or to have no friends at all.

—Today is worse than yesterday.

I felt that too. Worse than yesterday. I set to work on typing up the survey. I was in the middle of trying to decide which font would be the most therapeutic when Brenda called.

“How are you feeling?”

“Why?”

“I’m your wife. I can ask these questions.”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, that’s an improvement.”

“Okay, I guess I feel like a robot that was programmed to believe it was a little boy, but that just cut itself and to its dismay discovers it can’t bleed.”

“What the fuck does that mean?”

“I don’t know what the fuck it means. What about you? How are you feeling?”

“You shouldn’t swear at work.”

I could hear people in the background at her work typing and talking business. Brenda works in marketing. She is Senior Sloganeer. She has done very well. She ascended quickly because she scares the shit out of people. I can’t say exactly when this started. There may have been a makeover in there. Aggressive outfits and high-tech weekly planners suddenly appeared as if they had always been a part of her life. Maybe some of it was accidentally added to her personality when she got hypnosis to help her quit smoking. Or it might have happened around the time she became concerned with something she referred to as her “core.”

“I saw a man that looked like your father panhandling under the President Truman Overpass on the way to work,” she said. “I just thought I would tell you.”

“Oh.”

“What are you working on?”

“Something important.”

“Don’t get fired.”

I tried to hang up first, but she beat me to it.

I added a few more questions:

—Have you ever fallen in love?

—If yes, were you surprised that it, like all other things, faded over time?

—Would you equate this to the way that gum loses its flavor, or more to the way all food loses its heat?

I looked over the questions, checking for spelling errors. I read them aloud, but very quietly, to myself, to make sure they made sense. I decided on a title that I hoped would lend an air of institutional credibility—“Emotional Well-Being Self-Appraisal”—but it still wasn’t enough. After a little internal brainstorming I added: “Please complete forms within forty-eight hours and return to the desk of Raymond Champs, Senior Pictographer, Row 8, Pod D (Customer Acclaim, Employee Regard, Product Elucidation, Quantity Assurance, and Technical Support). All information will be treated as confidential.” I read it back to myself several times. Would I believe it was an official document had I not written it? Would I get caught? Was this a good idea? I looked up at the child soldier’s photo, and his hardened child eyes seemed to say, How the fuck should I know?, while also saying, Why the fuck should I care? He made a compelling argument holding that automatic weapon. I sent the document to print at the laser printer over on the south wing. Fifty copies.

Along the narrow corridor to the laser printer, the wall to my left was real. Real drywall painted a forest green, with windows looking into empty conference rooms. On my right was a series of three-quarter walls that could be reconfigured at the whim of a middle manager. As I walked past, I was able to steal glances in; my colleagues were all tucked into their stations like sailors in their bunks. They all shared a universal slump, their backs to me, their heads bending in toward the glow of their screens. Their hearts had slowed down. They were barely breathing. Soft, inert bodies with all motion isolated to one little hand clicking on one little mouse. That was their only motion, and it was incessant. They reminded me of hamsters sucking on water bottles, but they were clicking and clicking and clicking instead of sucking and sucking and sucking.

Nora Pepperdine was at the printer talking to Charlie Danglish. They were laughing. I didn’t like the way he leaned in toward her. He was married. He wasn’t young, but he was still athletic and attractive enough to sell things. He had broken the record for most hideaway beds sold in a year, a record he had set himself the previous year. His sales successes catapulted him to the head of the Customer Acclaim department. People, but not all people, tended to like him. He had a disarming smile. He spent a lot of money on dress shoes.

Nora was the object of all of our fantasies. No one needed to confirm this. It was in all of the male eyes, and many female eyes too, whenever she stood up to offer a little pep at one of the all-hands meetings. She had the perk of an Olympic athlete. I hated the perk, but sometimes I imagined myself pressed up against it, asphyxiating myself in the high altitudes of her exuberance.

They were reading my survey. The fresh stack had been waiting at the printer unprotected. That was why they were laughing. Nora’s sparkling curls were laughing along with her, and Charlie was still leaning in. He put an arm on her shoulder, as if she might need some support while she laughed. In his laughing mouth were perfect white teeth. I looked at his perfect teeth and imagined the skeleton beneath the salesman flesh.

“I see you have the survey everyone is talking about?” I said it cool. I was focused. This was important.

“Raymond,” Nora said, though I had told her so many times she was welcome to call me Ray. “What do you know about this? It’s very unusual.”

“How does it make you feel to read it?” I asked.

They looked as if they didn’t see the connection between reading a survey on feelings and having feelings.

“All I know is I heard that everybody is meant to take it,” I said. “It’s part of our biquarterly assessments, not as a measure of our performance but merely as an opportunity to check in and make sure we are all doing fine, emotionally that is.” It was a fib, fluttering out of my mouth like a moth in search of light. I added, hoping it might help convince them, “They don’t want us to feel any of this low, quiet crushing that some suspect might be going around.”

Charlie’s hand awkwardly remained on Nora’s shoulder for a moment, until it looked out of place. He must have sensed this. He slowly retracted it and put it in his pocket, and when that wasn’t right he crossed his arms against his chest. They both looked at me, uncertain.

“But I could be wrong,” I said. “All I know is that I heard Jerry Samberson really wants us to take this seriously, put some thought into it, and open up as much as possible.”

Jerry was our boss. People joked that he was born in the company nursery, though I’ve also never heard it refuted. I don’t think I have eve

r seen him leave the campus. He was the one who thought we should call it a “campus.”

I stared at Nora a little too long after I had said all of this. I got lost in her curls. They were like ribbons coaxed into coils by master gift wrappers.

I sensed Charlie staring at me staring at her.

I broke the silence. “Do you mind distributing the survey along your aisles? I am sure Jerry will appreciate it. I have to get back to diagrams for the new reversible book closet they are pushing for the holidays.” I turned away before they could answer.

• • •

I worked on some drawings to get my mind off of the survey. I was at it for over an hour. I must have thrown away five or six drafts. The man I was trying to draw, the man I always draw, Mr. CustomMirth®, wasn’t his usual self under my distracted hand. His potato-shaped body was not whimsical enough. It was agitated and shaky. Impatient. His balloon nose was edging perilously on the brink of ethnic. I was unable to work. All I could think about were the answers that would come back to me. And then all I could think about was how exactly I might go about alerting the world to its own infection. Who would listen to me? How could I continue to work while sending out the distress calls? If I wasn’t working, how would I pay for a full-page ad in a major periodical?

I heard a throat clear and smelled the thaw of company bagels. Don Ables had entered my cube. Don worked a few cubes down, where he worked harder than anybody else. He was a soft man with milky flesh and hair that stained pillowcases. He lived with his sister. One of them took care of the other. Nobody had met the sister. There was a terrible photo of her on his desk that we all tried not to stare at. The light in the photo was all wrong. Her face was mostly shadow. You couldn’t tell how many eyebrows she had.

“Hello, Don.”

He looked unsettled.

To break the silence, I said, “In the science-fiction movies you watch, what do the townspeople do when they discover something monstrous from beyond is breeding in the municipality’s waste treatment plant?”

“Is this some kind of cruel joke?” He was holding the survey. His small gray eyes looked pinched.

“I’m not sure what you are talking about,” I said. I knew exactly what he was talking about and was encouraged by his distress.

“Nora came into my cube and put this on my desk,” he said. The words came from deep within his chest. His belly quivered. “At least four of these questions are explicitly targeted at me.”

I had never seen Don so upset. Until that moment he had struck me as somebody who, however miserable, felt a certain sense of relief because he would never have to attend high school again. His presence no longer evacuated lunch tables.

“She said that you were collecting them. I don’t understand what this is about.”

“I don’t either, Don.”

“I don’t like it.”

For a split second I betrayed myself with the slightest smile, because I was pleased that my questions were uncovering these feelings in Don, but I quickly transitioned to a sympathetic nod, which I hoped masked any trace of authorship. He placed the survey facedown in the workspace opposite my computer. I heard his shoes squeak as he walked back to his cube. I thought I could hear his office chair react to his weight. I listened for his tears, or cries, or perhaps a distraught call to his sister. Then I simply began to listen. People coughed. Throats were cleared. Fingers typed. There was whispering through walls. The north entrance beeped as somebody either entered or exited. The lights above hummed in all their institutional cheapness. Deep within the humming I thought I heard a foghorn half a continent away. Everything I thought I heard began to sound muffled by mist. Beyond the horn I heard my mother telling me it was too dark outside to play. Yelling at me from the front porch of our old house, the yellow one with the ivy growing up the sides. Yelling up and down, left and right, because it was quickly dark, and in shadows I could be anywhere and anything; I could be behind the parked car, I could be hiding in a shed, I could be up in a tree. She said, as if talking down a wild cat, “Come in and watch Love Boat.”

Would you prefer to be someone else?

I am not sure that I am even me anymore. To be good at my job, I must eliminate feeling, surprise, and abstract thought from the creative process. It’s like being told to kiss a beautiful woman but that you must under no circumstances let it arouse you. When you start the job, you tell yourself it is merely a matter of compartmentalizing these things. You put them in a drawer, somewhere inside of you—the passion, the inner thoughts that drive you and inspire you, the dreams that are too pure to decipher, that tell you to paint a sky yellow, or to draw a woman laughing in the rain with hair on fire, or any other crazy thing that is beautiful because it barely makes sense. You tuck these parts of yourself away for safekeeping, and years later, when you are on vacation, on maybe the third day of the vacation, when you have exhausted all of the entertainment features of the resort and you find you have nothing else to do, you open up the drawer, just to check in on those organs of emotion you have stored away, and you find they have shrunken and dried out like an old dead beetle.

I drew up an official-looking sign with “Surveys” written on it and an arrow that pointed to a wire basket I had stolen from the supply cabinet. In the basket I placed a large manila envelope upon which I had written “Confidential.” I put Don’s survey in there. I wanted to read it desperately, but I didn’t want to get caught reading it. Somebody passing by or dropping in with a question could catch me in the act. People needed to believe this was coming from the top.

The phone rang. “Are you still working on something ‘important’?”

“Hi, Brenda.”

“You didn’t tell anybody about the robot, did you?”

“What?”

“The robot that doesn’t bleed, or whatever that gibberish was earlier.”

“Are you starting to feel that way too?”

“I often feel like a machine. It’s called getting shit done.”

I wrote this down on a pad of paper. She might be a lost cause.

“But listen, Ray, you didn’t tell people at work that, did you? That you are a boy robot? Don’t start talking like that at work. You can say that nonsense to me, because we have a legally binding agreement that I won’t leave you in sickness or health. But they’ll dump your ass faster than microwave popcorn if you start talking like that.”

“I haven’t had a meaningful conversation with anybody here in over ten years.”

“Good. We recently fired somebody for saying he believed the earth has a consciousness.”

“What?”

“Exactly. Right in the middle of a team-building breakfast. He was packing his things before lunch.”

“I have to get back to work.”

“That’s the spirit.” She hung up.

More surveys trickled in while I worked on a drawing for our new whisper mop. I was trying to give the mop a face. The face was to look up and wink at Mr. CustomMirth®, who was mopping up a spill. I was pleased with the face on the mop. It was playful and compliant. The spill, however, looked too much like something regurgitated, a hearty stew come back from the digested. I crumpled up the drawing and stared blankly at my computer.

I needed a break. I peeked out into the aisle, and when I was sure nobody could see me I grabbed a completed survey from the envelope and snuck off to the company gym.

The gym was all mirrors. A kaleidoscope of white metal fitness machines. I grabbed a communal magazine stacked next to a chain of stationary bicycles. I was the only exerciser. I could see at least twelve of my selves: pale limbs, flushed cheeks, flimsy bodies.

Concealed in last September’s issue of Man Health, I took a look at Van Wilson’s self-appraisal. Van was a nepotism case. His mother was best friends with Jerry Samberson’s mother. Van wrote:

I think we should have more sport

s. I think if a guy is really good at some sports, like riflery, then he should get credit at work and at home, because it shows he can focus and really make something happen.

It made me dizzy to run and read at the same time. I slowed the treadmill to a brisk walk, climbing a hill ranked level three. I noticed in the reflections that my hair in the back was melting away into a circle of unprotected scalp. These mirrors defied my active hair-loss denial.

I read more:

I am totally a Monday, because Sunday, when it isn’t football season, I work on things and play virtual golf and kind of get in touch with stuff, and I’ll call an old buddy and drive my car around and sometimes walk around the mall, just kind of getting to know my thoughts and checking out sales and magazines, and then I go to a movie or maybe catch a buffet somewhere. So I am more or less Sunday—that is my day. I am Sunday. But since that isn’t a choice, I figure Monday is closer to Sunday than Wednesday, unless you say that the week starts with Monday and you can’t get to Sunday until you have gone through Wednesday, but I don’t think that’s what you mean by this question. I see the week as more of a wheel, and that is why I am closer to Monday than Wednesday. I am a Monday.

Van was probably in denial. That was okay. I should have expected this. A likely symptom of the epidemic.

The men’s locker room was empty. It smelled like bleach and dirty socks. Sports-themed music was coming out of tiny round holes in the carpeted ceiling. I decided to take a sauna. It is the one place in all of the buildings that isn’t air-conditioned.

I sat on the top bench, wearing my towel like a skirt. I ladled water on the rocks. They hissed. I sat and wished that I could travel back in time and get a representative sample of depressed people through the ages. My research could benefit from some graphs. I wanted to chart the course of humanity’s collective spirit over time. The Middle Ages might have been a low. That could be good news. This might be cyclical, like sunspots or El Niño.

Why Are You So Sad?

Why Are You So Sad?