- Home

- Jason Porter

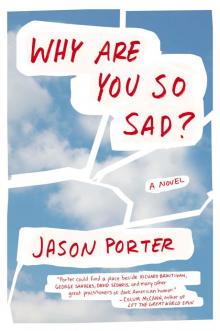

Why Are You So Sad?

Why Are You So Sad? Read online

A PLUME BOOK

WHY ARE YOU SO SAD?

©ERIC WHITE

JASON PORTER was born and raised in southeastern Michigan. He is, or has been, an English teacher, customer support representative, landlord, traveling musician, and the overnight editor for Yahoo! News and the New York Times. Currently, he writes fiction. Why Are You So Sad? is his first novel.

* * *

Praise for Why Are You So Sad?

“Why Are You So Sad? is wry, sardonic, very smart, and hilariously critical of the futility and general mediocrity of life in America as we know it.”

—Patrick McGrath, author of Asylum and Constance

“Why Are You So Sad?: Why are you so funny, so wry, so true, so compelling? Jason Porter’s lovely book is perfect and wondrous, a masterfully crafted story of modernity. I ate it whole.”

—Jennifer Traig, author of memoirs Devil in the Details: Scenes from an Obsessive Girlhood and Well Enough Alone: A Cultural History of My Hypochondria

“Existential despair has never been so funny. Why Are You So Sad? is a great American comedy, perfectly tuned to this ridiculous age. Jason Porter is a Kafka with better jokes.”

—Larry Doyle, author of I Love You, Beth Cooper

“Why Are You So Sad? is a precisely calibrated comedy pitched halfway between a laugh and a sob. Beautifully written, philosophically unsound, and funny.”

—Sara Levine, author of Treasure Island!!!

“Porter starts with a loaded question and takes aim at our compromises and deferred dreams, at our unquestioned normalcy—and he hits us where we live. But this is Camus crossed with Stanley Elkin, a brilliant book that’s as funny as it is wise.”

—Jeffrey Rotter, author of The Unknown Knowns

PLUME

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Plume, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Jason Porter

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

ISBN 978-0-14-218058-7

ISBN 9781101632055 (eBook)

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

PART ONE: SHORT ANSWER

PART TWO: MULTIPLE CHOICE

Acknowledgments

For Trucker, Petey, and Shelly

The present generation, wearied by its chimerical efforts, relapses into complete indolence. Its condition is that of a man who has only fallen asleep towards morning: first of all come great dreams, then a feeling of laziness, and finally a witty or clever excuse for remaining in bed.

—SØREN KIERKEGAARD

PART ONE

SHORT ANSWER

I was in my bed when the thought came to me: Have we all sunken into a species-wide bout of clinical depression? A severe, but subtle, despondency, germinating in every single one of us. The thought hit me. Smacked me as true. Its flawless pitch rang on and on, adhering to my consciousness like shit on shoe.

I was on my back. My hands making a tent on my sternum. I was staring at the ceiling fan spinning above, its body wobbling gently in reaction to its rotating blades. It was a sort of meditation, focusing on the blades; an attempt to quiet my senses and fall into sleep. As if the thought were not distracting enough, a car alarm went off outside. A squawking robotic bird with Tourette’s syndrome. But I pressed on. Still committed to easing my mind, I endeavored to appreciate the beauty of the silence that existed between the beeps and screams of my neighbor’s BMW. It was a nearly impossible task, but in those spaces I did find something. I found the calls of the dead. I found the dinosaurs. They said, It started like this for us too. We were down. Nobody noticed because it was gradual. It snuck in like fog. We were moody and sluggish and complacent, and we were too busy eating things to take notice.

In time the car alarm relented. I stared with even greater focus at the ceiling fan. I could hear the buzz of the lighting element in the reading lamp. I was aware of every hair on my body. I itched. I knew that at the very least, I was depressed. I wondered if the depression had always been there. It was not unlike listening to the song “American Pie.” You reach a point in the song when you ask yourself, “Have I always been listening to this song?” To answer yes defies rationality, but to answer no discredits your experiential reality.

I reconfigured. I fluffed the pillows. I got fetal. Closing my eyes, focusing inward, I tried to call up something cheerful that might set my thoughts on a hopeful course—a giggling infant, the toss of a wedding bouquet, a grandfather happy to receive a call from his grandson—but all I could think of were third-world viruses that sold newspapers and dissolved brains. I quickly composed a mental catalog of friends, colleagues, former roommates, elderly neighbors, and the anonymous faces who sell me gasoline, deliver my mail, and fill my prescriptions; I uncovered alcoholics, overwhelmed parents, hoarders, diet addicts, news junkies, tabloid gobblers, sexless marriages, teenage diabetics, cell phone dependents, and uninsured back pains resulting from unresolved childhood rage.

I rolled over to get my wife’s opinion. She was lost in a gigantic children’s novel. Her brown eyes, even bigger behind glasses, were scanning the pages left to right. In her glasses I could see the whole room reflected. I could see the white curtains we bought at a bargain through my employee discount, the matching dressers purchased through the same discount, and a fern that wasn’t thriving. I took turns looking at her through one eye while the other was closed, toggling back and forth. From both perspectives she didn’t seem to notice I was staring at her.

I said, “Brenda, is it me or is every single person we know depressed?”

She let out a dramatic sigh and slowly closed her book. She didn’t want to leave the story. As she turned to look at me she spilled a little bourbon. It’s a habit of hers. It dribbled down her chin and onto her nightgown. She kissed me on the forehead like she was putting a stamp on a letter, and said, “You are.” And then as she turned off her light and shifted onto her side, facing away from me, she said, “I’m not.”

She wasn’t one to dress things up. I let what she said settle, but it did nothing to calm my anxieties. I inched over and held her. She didn’t feel dead. Nor did she feel awake. I then reached past her, taking the bourbon from her nightstand, almost knocking over her alarm clock. Like a baby bird being fed by its mother, I held the glass over my mouth for every last drop, enjoying the harsh warmth in my throat and chest.

The bourbon made no difference. I stared at the ceiling fan for hours.

Are you single?

&nb

sp; No, I am married to Brenda Champs, formerly Brenda Brynschzchvsksy. She took my name, Champs, not out of some nod to tradition, but because she hated having a name nobody could ever pronounce, including her new husband, me. It certainly wasn’t for the children, because we don’t have any.

The following morning I found myself no less preoccupied. I was driving to work. My car stereo had been stolen the previous week. I could hear my thoughts too clearly: That man driving that car is sick. That other man driving that other car is sick. I am sick. We are all sick. Something is in the water. It is in the soil. We are all symptoms of a grieving planet.

I was coming up on the backup to the General Eisenhower Bridge. We were all merging to pay the toll. Traffic choked on itself here without fail. Red brake lights flickered. Drivers were greedy about their lanes. Their despair and emptiness reached out to me through the glass and steel and molded plastic. I could feel myself in each car. I was for a moment each of these people. I felt it all. And it was their breath mints that pushed me over the edge.

I realize that sounds a little crazy. But hear me out. I heard their talk radio: awful. I chewed on their fingernails: mindless. I sipped on their lukewarm coffee while gazing at their reflections in the rearview mirror: hateful. I felt the way they dreamed about what might happen next in their lives: lonely, depressing, barely imaginative. But nothing was worse than the breath mints. I carefully imagined breaking them down with my tongue. Pressing them into the roof of my mouth. It tipped the scales. It was revolting. They tasted as if the chemists who design all of our commercial food additives had developed a purely artificial flavor that was in itself the absence of flavor. They were minty, sure, but in such an intentionally absent way. Hardened on the edges by the sharp chemical nontaste of erased calories. It was absolutely horrid. The fact that all these people could suck on these mints, driving along in a limping herd, actively not tasting things—it overwhelmed me. Completely. This was disease. Rot. Evolutionary peril. My empathic sensors, or whatever the hell they were, were overheating. Watching the stuttering cars, and all the miserable, unsuspecting people trapped inside of them, it became obvious that I needed to either confirm or disprove my suspicion. I needed to get some irrefutable science behind this. Otherwise it risked carrying on in my mind like a phantom odor: What is that smell? Is something burning? Maybe I am only imagining that something is burning? Am I imagining that something is burning? Am I burning?

What I needed was an emotional Geiger counter that could objectively measure other people for sadness. I looked at the woman in the car next to me. She was applying makeup during the stops, opening and closing her mouth like a feeding fish, staring at her red lips in the rearview mirror. I imagined holding the Geiger counter to her forehead. I would ask her a question about her children. Were they an accident? What dreams did they make impossible? She would say, “They are the best thing I ever did,” and the readout would expose her lie with a pixelated frown.

Starting up the bridge, I looked down at the water. It was the bottom of the bay, where the filth comes to die. Twigs and feathers and candy wrappers were suspended in a gray foam that was undulating along the shoreline. Ahead of me, the sun, charcoal orange and hazy, was beautiful like a bruise. It was hot, and it smogged down on me past housing projects and strip malls and strip clubs and furniture marts, into a shifting desert of corporate parks. About a mile short of our offices, I passed a billboard for a vacation resort that said “Put Your Dreams to the Test.” The words were paired with a picture of a doctor in a Hawaiian T-shirt holding a stethoscope up to a piña colada. It was the stupidest thing I had ever seen. I couldn’t make any sense of it, but the word test stayed with me. A test. An exam. A questioning.

Which led me to my decisive course of action: I would take a random sampling at work. All the necessary data was waiting for me in the office. It was too simple. The people there are compliant. They do as they are told, like sheep waiting for paychecks. Corralled over to meetings that serve no purpose. Filling out forms they never hear about again. Sitting in on career-development workshops with box lunches and guest speakers who had just flown in from the middle of the country. It was a natural fixture within the terrain, jumping through unnecessary hoops. If I were to ask a few personal questions, assuming the formatting was authoritatively insipid, nobody would be the wiser. That was the plan. I would compose a survey, deftly crafted to root out the true feelings of those around me. If the sampling supported my fear—the gradual but certain emotional demise of the world’s population—then, well, I didn’t know. I would have to do something. Reprioritize my life. Circle the wagons. Notify the authorities. Conduct more focused research. I would give the epidemic my full attention. This might not be good for my career. I would have to work part-time or take a leave of absence. There would be definite and irreversible consequences. Brenda would not be happy, but who was?

I turned into the parking lot next to the sign for our offices that read “LokiLoki: Everyday Living Is Getting Better Every Day,” and found a space by a newly planted tree. The tree still had a tag on it. It was the shadiest spot available.

In the cramped discomfort of my Korean hatchback, I thought up questions that would trigger heartfelt responses from my colleagues. I found an empty brown bag under the passenger seat and scribbled down the following:

—Are you single?

—Are you having an affair?

—Why are you so sad?

—When was the last time you felt happy?

—Was it a true, pure happy or a relative happy?

The last question edged up against a greasy stain left by a pastry that was no longer in the bag. It looked like the word happy was going to enter a dark brown hole, as if the entire sentence was a train about to funnel into the side of a mountain. I thought briefly of caves. I imagined an afternoon stroll in the woods leading me to a hillside cavern, and curiosity drawing me in. I would lean against a wall at the very edge of where the outside light was lost to the world’s dark interior. I would pause, rub my eyes, adjust to the lack of light, and without realizing it find myself talking to a company of bats. Sharing ideas. Learning about each other’s worlds. It turns out they don’t particularly miss seeing things. I would say, “I think it is precisely because I see things that I trip over them.” The bats would laugh and fly directly at me and then around me and out into the evening.

I began to perspire. The sun, even through the haze, was stifling. The car was becoming a hot house.

I wrote more questions:

—Are you who you want to be?

—Would you prefer to be someone else?

—Are you similar to the “you” you thought you would become when as a child you imagined your future self?

—Is today worse than yesterday?

—If you were a day of the week, would you be Monday or Wednesday?

—What does it feel like to get out of bed in the morning?

A car pulled in next to me. I grabbed for my cell phone and pretended to be in the middle of a conversation: “No, no, no . . . That’s putting it mildly . . . Of course not . . . Yes, yes, yes . . . You tell me . . . Well, that takes the cake . . . Absolutely not . . . Are you deaf? . . . That is not acceptable.”

It was Bob Grasston. We started at LokiLoki on the same day more than a decade ago. I am a Senior Pictographer, North American Division. I draw the instructional diagrams for the assembly manuals. I can’t remember what Bob does, exactly—something involving charts and projections—but I see him every year when they call us in for flu shots. We have consecutive employee numbers.

He was in a cobalt blue sports car that didn’t suit him. It was too sleek. Too lecherous. It beeped as he waved his keychain, commanding the car to lock from a distance of several feet. I gave him a nod while I said, “You better believe I mean it,” to my phone. He paused, maybe thinking I would get out and walk with him, but then he went on down t

he footpath toward the Business Development Tower. He was carrying a briefcase and a gym bag. The way his belt cinched his dress shirt into his slacks made him look doughy, like a pork bun with a goatee.

I did some quick calculations:

—Do you realize you have on average another 11,000 to 18,250 mornings of looking in the mirror and wondering if people will find you attractive?

—Do you think people will remember you after you die?

—For how long after you die?

I paused and looked up for more inspiration. The windshield was covered in dead insects. I wondered what it must feel like to have a speeding plane of shatterproof glass catapulting your exoskeleton into flatness.

—Do you believe in God?

—Do you believe in life after death?

—Do you believe in life after God?

—Do you hear voices?

—Are you for the chemical elimination of all things painful?

—Do you think we need more sports?

It was a good survey.

If you were a day of the week, would you be Monday or Wednesday?

I would be a Wednesday, but in a week that went Wednesday, Wednesday, Wednesday, Wednesday, Wednesday, Wednesday, Wednesday, and repeat.

Every aspect of our workspace was decorated in strict reverence to LokiLoki’s official colors: electric salmon and evergreen. Under the buzz of fluorescent lighting the colors could at times look radioactive. Walking through the maze of shimmering office partitions was like getting lost in a durably carpeted cornfield. Stalks of filing cabinets and impermanent desk dividers shot up taller than basketball players. Passing each row revealed another identical row, and the rows extended in every direction. I kept my bearings by looking for environmental markers within the cubicles. To get to my desk from the east entrance, I turned right at the puppy calendar, right again at the cross-eyed honor student, followed by a left at the fat black goldfish with the disfigured dorsal fin.

Why Are You So Sad?

Why Are You So Sad?